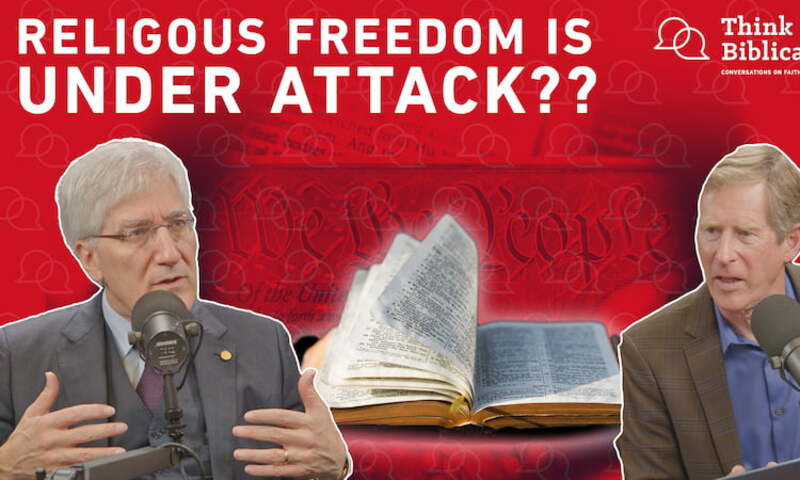

Is religious freedom the first and most fundamental freedom in a culture? Or is the claim for religious freedom simply code for various forms of bigotry? What is the state of free speech and the freedom to dissent on college campuses today. Join Scott as he discusses these questions and more with Princeton Professor Robert George.

Robert George is McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and Director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions. He has served as chairman of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), and before that on the President’s Council on Bioethics and as a presidential appointee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights.

Episode Transcript

Scott: Why is religious freedom so important? Why do we say that it's the most fundamental first freedom that we all enjoy? What do we say to people in the culture who insist that religious freedom is just code for bigotry? We'll answer these questions and more with our special guest today, Dr. Robert George, professor at Princeton University. And welcome. So glad to have you with us, Robbie.

Robert: Brother Scott, it's such a pleasure to be here with you. Thank you for inviting me onto the podcast.

Scott: So what makes you so passionate? I want to hear sort of personally from you. What makes you so passionate about the subject of religious freedom? You've written tons on it. Why has it been such a focus of your attention?

Robert: It's because I believe that people, human beings, men and women are made in the very image and likeness of the divine creator and ruler of all that is. That means that we have profound worth we have profound inherent and equal dignity. And as a result of that belief, I'm impelled to do what I can to uphold the dignity of human beings. And there's nothing more fundamental to the dignity of human beings than their right to raise the basic questions of meaning and value: the ultimate questions, the existential questions, the questions of whether there is a more than merely human source of meaning and value, whether there is a God, what does God require of us? And then to answer those questions as best one can, honestly, and to live with authenticity and integrity in view of one's best answers to those questions. If we do not permit people to do that, if we permit that fundamental right to be trampled, then the dignity of human beings, these precious creatures made in the very image and likeness of God is undermined.

Scott: Now our dear mutual friend, who's since gone to be with the Lord, Chuck Colson, insisted that religious freedom is the first and most fundamental freedom that human beings enjoy and that all of our other freedoms emerge from that. How would you defend that notion that religious freedom is not just one of a host of freedoms that we enjoy, but actually the most foundational?

Robert: Well sometimes religious freedom is called the first freedom, especially by Americans, because it's the first freedom mentioned in our Bill of Rights, in our great charter of freedoms. The First Amendment says that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or the press, or the right of the people to assemble and petition the government peaceably for a redress of grievances. So religion is listed first. But that's not the reason it's most fundamental. It really works the other way around. I suppose it was the judgment that there is nothing more important than the freedom of conscience, the freedom of the mind, the freedom to inquire about God and to live in line with one's best judgments about what God requires of us. It's because of our founders' judgment of the fundamental nature of that freedom that they placed it first, even before freedom of speech, even before freedom of the press, even before the right, very important right, to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances.

Scott: Now you've written on several occasions that the Founders were also good students of history and that they understood what happens in cultures and in nations where religious freedom is not respected. So tell our listeners a little bit about the background that the Founders came out of, which heightened their appreciation for the role of religious freedom.

Robert: Well, of course, one of the things that they knew from history is that where religious freedom is absent, all other freedoms disappear. In that sense, religious freedom does appear to be, at least from our historical experience, foundational and necessary to the preservation of other freedoms. Now, it's not exactly the same thing as freedom of speech, or freedom of the press, or due process of law, or the equal protection of the laws, but it's fundamental in those civil liberties from the historical perspective because when it disappears, everything else goes along with it. Now our founders also knew that people could, where there were religious differences, fundamental religious differences, turn religion into a reason to resort to violence with each other or turn religion into a reason for oppression or repression. They were very concerned about that. They knew that they were founding a pluralistic country. It was mainly Protestant Christians at the time, but the difference between the different denominations was considered pretty deep and pretty wide. There were a small number of Catholics and a small number of Jews. There was a very small number of Muslims here at the time and some others. But basically their culture was one in which you had congregationalists and Episcopalians and Baptist, different Protestant denominations who took their differences very seriously. And the Founders did not want those differences to be the impetus for civil strife, civil unrest, conflict, or repression. Some have inferred from that that our First Amendment guarantee of religious freedom, the American principle of religious freedom is what is sometimes called an article of peace. But I think it's more than just that. I think religious freedom was understood by our founders to be necessary, not simply because if we didn't respect it, we would end up with war, civil war, civil strife over religion. If you read Madison on this subject, or you read Jefferson for that matter, who was the least religious of the founders, he was not an atheist. Sometimes he's accused of being an atheist. There's a certain sense in which you might say he was a deist or a Unitarian, but not a deist even in the modern sense of that term. But even someone like Jefferson fully understood the existential importance of raising religious questions, answering them honestly, and living with authenticity and integrity in view of one's best answers. And so a Jefferson, a Madison, or other founders could appreciate importance of religious liberty, not just to the maintenance of civil peace and order, but also to the flourishing of human beings as creatures who are naturally askers of religious questions. Human beings as creatures who naturally aspire to know the truth about ultimate things, the truth about God, and to get themselves right with God, to get themselves in line with what God requires of us. We might say, into friendship with God. Our founders themselves, of course, had different views about religion. Some were more religious, some were less religious, some were certainly what we would fully call today Christians, others were not. But I think broadly among the founders, there was an appreciation of the existential importance of religion understood in the way that I've just described it.

Scott: So the founders, they had prudential concerns based on their history because they'd seen violence occur so often, but it sounds like they also had a good theological understanding of a human being.

Robert: That's right. I mean, Madison's own discussions, for example, of the importance of the freedom of the mind, that we couldn't really have faith in God if it was compelled, that a compelled faith is no faith at all. I mentioned this morning in remarks I made here at Biola in my chapel address that we can, government can, law can, power can compel the external acts that are sometimes the manifestations of true faith. You can force somebody to go to a church service. You can force somebody to attend a Passover Seder. You can force somebody to go to the mosque. But you're just forcing outward behavior. What you can't reach, what law, what the state, what government, what power cannot reach are the internal acts of intellect and will that are the very substance of faith. Going to the mosque, going to the church, going to the synagogue, those are manifestations of faith. They're very important. They're not mere window dressing, they're the real thing, but they only have genuine meaning and substance when they reflect internal judgments, internal acts of intellect and will that are the real substance of faith. This is why we can have faith even if we're locked in solitary confinement in a prison cell, we have no access to a clergyman, we have no access to the Bible or to the scripture of our religion, we have no access to a religious service. We can still perform the acts of intellect and will that are the very substance of faith. And even in circumstances of complete freedom, if I'm just falsely manifesting faith, maybe because in my culture manifesting faith is necessary for me to be in business or to get ahead or for political reasons or whatever, that's not real faith. Going to church, just going to church is not real faith. Going to church because I judge that the Lord wishes me to worship him in this way, in this place, in this manner, that's real faith.

Scott: Right. Now, we've known for some time that religious freedom has been under assault globally. Now, the stories of the persecuted church have been well publicized. And we gave our own Colston Award to brother Andrew several years ago who-

Robert: Wonderful.

Scott: Wonderful man. But we hear more conversation today about how religious freedom is under assault in the West, in the United States in particular. What do you make of that claim, that religious freedom is under attack today in the United States? Is that true?

Robert: Yes, it's certainly true.

Scott: Okay, what's the evidence of that?

Robert: Well, the evidence is laws, for example, that would compel a Christian or Orthodox Jewish or Muslim physician to perform or refer for or be trained in the practice of abortion, that would compel a Christian florist or website designer or musician to participate in a celebration of a same-sex relationship that, according to the religious faith and conscience of the individual, he or she could not approve and participate in. You see this in efforts to use anti-discrimination laws to compel conformity with secular progressive doctrines, which are directly contrary to the Christian moral understanding of things. So yes, religious freedom is under assault in the United States. Now, thank God nobody is being killed in the United States for their religion, and that is happening in other places in the world. When I was serving, so this would be back in 2016, I haven't checked the figures since then, But when I was serving as chairman of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, we found that something approaching three quarters of the world's population lived under regimes that were in serious ways disrespectful of basic rights of religious liberty, whether we're talking about Buddhists in Tibet, house church Christians and others in China, whether we're talking about the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, whether we're talking about the Ahmadiyya Muslims in Saudi Arabia or in Pakistan, whether we're talking about Jews in various places, whether we're talking about Evangelical and other Christians, Catholics and others in other places. That's a lot of the world's population living under regimes that repress their free exercise of religion. So we've got a problem. We've got a problem in the world and we've got a problem in the country.

Scott: Yeah. Sometimes I think that that, that stark contrast between what's happening in other parts of the world where people are being imprisoned and being killed and churches are being burned and you know, I mean all sorts of terrible things are happening to people of all religious stripes. I mean, I think about the, the Uyghur Muslims for example, in China.

Robert: That's another good example.

Scott: You know, where they, the estimate is close to 3 million of them live in something akin to concentration camps.

Robert: Yes, and are subjected to terrible atrocities such as the removal of organs for transplantation, commercial sale. It's just a nightmare and we don't hear enough about what happens to those and other religious minorities around the world.

Scott: I think the fact that there's such a stark contrast, I think would lead some folks to take the assault on religious freedom in the US, maybe not quite as seriously. Because you think, well, you know, what are you complaining about here? You really have it pretty good compared to the way religious believers are treated in other parts of the world.

Robert: Well, we're rather fond in our country of our basic constitutional principles. We really do believe, we hold as self-evident that all men are created equal, endowed with their creator with certain unalienable rights, and among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We believe in our First Amendment. We believe in our constitutional principle of no religious test for public office. We're committed to these things and we're right to be committed to these things because these are true and good principles. And when we see these principles being eroded, often in subtle and insidious ways, it really is up to us to defend the American experiment in ordered liberty. Our founders understood that what they established here, this Republican form of government, this system of ordered liberty was an experiment, it might or might not work. And it would only last if each generation was zealous in its protection of the basic understanding of civil liberty, the basic constitutional order, the constitutional structure that they would bequeath to us. And it really is our duty. It really is our responsibility. If someone's rights to religious freedom are being violated by government at any level, then it really is incumbent on all of us, no matter how small the violation appears to be, to say, "No, we're not putting up with that. We're not going to stand for it. There are mechanisms for political redress in our constitutional system, and we are going to avail ourselves of those mechanisms, and we're going to set right the wrong." But it's really important that we do that for everybody, not just for the people of our own faith. I, as a Christian, should be speaking out in defense of the rights of my fellow Christians when they are violated. But I, as a Christian and as American, also need to be speaking out for the rights of Muslims, the rights of Jews, the rights of Buddhists, the rights of Hindus. It doesn't matter what their faith is. Our responsibility is to protect their basic right to practice that faith.

Scott: You know, and including people who express no faith.

Robert: Exactly right, that's right. As I said in my Biola address this morning, the morning we're recording this, even atheists have a right to religious freedom. Some people think that's odd. How can they? They don't believe in religion, they don't believe in God, how can they have a right to religious freedom? But they have the right to raise fundamental questions, to answer them as best they can honestly in their very best judgment, and then to live with authenticity and integrity in view of their best answers. And if their answers are, I don't think that there is a Supreme being, I do not think that there is a personal God, then we have to respect their right to reach that conclusion in good faith and to act in line with that conclusion. So long as, what applies to absolutely everybody, they respect the rights of others.

Scott: Right. Now, Robbie, one of the, I think, more subtle ways that religious freedom is being challenged today in the West is by the impetus toward same-sex marriage and sexuality, the sexuality trends that exist in the culture. And we hear frequently that quote, "Religious freedom is nothing more than code for bigotry." That it allows religious believers to discriminate against gays and lesbians, in particular in their view of marriage. How do you respond to the folks in the culture who say that this is just another code word for bigotry and prejudice?

Robert: Well, that sounds to me like bigotry and prejudice, claiming bigotry and prejudice. The fact of the matter is people who believe in the dogmas and doctrines of the sexual revolution have embraced a religion, a worldview, a pseudo religion. They've got a system of meaning and value. They have an understanding of what's important in life. They have a system of values that conflicts with and competes with others, with the Jewish, with the Muslim, with the Christian understanding of ultimate matters and basic moral questions. We have no right in advance of a proper exercise of the democratic process, we have no right to simply declare ourselves to be the victors, but they have no right to simply declare themselves to be the victors or to use the mechanisms of law to repress the rights of other people. We have to make a decision, any culture has to make a decision, what will we legally recognize as marriages? Will we legally recognize only what we as Christians would call genuine conjugal marriages, the conjugal union of husband and wife? Or will we count as marriages polygamous partnerships? Will we count as marriages polyamorous unions? The difference being polygamy is one man in separate marriages to two or three or four or more women. Polyamorous so-called marriages, being marriages between groups of people. So three or five people of whatever sexes are married together in a sexual ensemble.

Scott: So any mix.

Robert: Yeah. Now society's got to make a decision about that. We have constitutional mechanisms for making the decisions. I happen to think those mechanisms were hijacked by an improper exercise of judicial authority by the Supreme Court of the United States in the Obergefell opinion, imposing same-sex marriage on the country, rather than leaving it where the Constitution actually leaves the question to the people acting through the normal democratic process, through their elected representatives or in states like California through referendum and initiative. But every society's got to make a judgment of that one way or another, and it simply will not do for people on the competing sides to try to dismiss the right of other people to participate in that democratic process by labeling them as haters or bigots or anything else. We've got to deal with each other's arguments. It would be wrong for me to respond to a good faith argument in favor of same sex marriage by saying, "Only perverts believe that." That would be wrong. I wouldn't do such a thing. But they are under the same obligation not to respond to genuine good faith arguments for the conjugal view of marriage by saying, "Only a bigot would believe that. You people who believe in marriage as a man and a woman are bigots." That's just an improper, unfair, illicit way of trying to win outside the democratic process.

Scott: In academic circles, we call those ad hominem arguments where you attack the person and not the position. I had a friend of mine who said that an ad hominem argument is where a person sits on the horns of a dilemma and decides to shoot the bull instead.

Robert: (laughing) Yeah.

Scott: And I think there's something to that. In academic circles, we consider those arguments to be sort of the last bastions of the intellectually desperate. That's the only resort to those as the last resort. Today we're resorting to those as a first resort. But I think the goal is the same. And that's really insightful to say the goal is actually to exclude participants from the democratic process of making their views able to be heard.

Robert: It's trying to declare victory ahead of the game being played. Or it's like a pitcher declaring himself to be the umpire and then calling 27 batters up, 27 batters down on three strikes each time.

Scott: Yeah, and I won that contest. Now, closely related, I think, to religious freedom is this notion of free speech. In particular, we hear a lot of debate about the place of free speech on college campuses. If you had to describe for our listeners the state of free speech on the average state university campus or the average private secular campus, what would you say?

Robert: It's perilous. The state of free speech is perilous. People are afraid to speak their minds. People are afraid to dissent from the prevailing orthodoxies, which are overwhelmingly secular, progressive or liberal dogmas on their campuses. Not only are students afraid to speak, faculty members are afraid to dissent. They may have qualms about whatever the latest woke dogma is, transgenderism or whatever it is, but they keep their mouths shut. They censor themselves. They engage in self-censorship because they fear the consequences, professionally or personally or both, of speaking their minds. Now, universities can't work in atmospheres of fear and intimidation. They just can't work. The whole point of a university is to be a truth-seeking institution. The truth is the goal. The truth is the telos. The truth is the reason we have universities. We're trying to deeper and more deeply and deeply, more and more deeply understand the truth of things. We're trying to root out error. And to do that, we need the freedom to think, to inquire, to investigate, to argue, to criticize. And once that freedom is erased, whether by formal mechanisms of law or by the suffocating atmosphere of public opinion, you are no longer in the truth-seeking business. What happens when truth-seeking leaves the scene? What happens when we're not doing truth-seeking anymore? What are we doing in universities? We're doing propaganda. We're propagandizing. We're indoctrinating. We're not teaching. We're not encouraging students to think for themselves. We’re stuffing their heads full of whatever our own favored dogmas are. No learning takes place. Knowledge is not advanced. The truth is not, our understanding of the truth is not deepened. So the situation on college campuses today is that we've, we're undermining the very justifying purpose and constitutive aim of universities by allowing this spirit of intimidation and fear to, this atmosphere of intimidation and fear to maintain, be maintained on campus. So we've got to do something about that. We have to overcome self-censorship. We have to make sure that people feel free and indeed are free to raise questions, speak their minds, criticize, defend, critique.

Scott: Based on your deeply held religious views and your deeply held conservative political positions puts you at odds I think with the prevailing winds in the secular university. How have you been able to, yourself, been able to battle some of those really strong headwinds that I suspect you've had to deal with in your tenure at Princeton?

Robert: Well, I've always just spoken my mind. I spoke what I believe to be the truth as God gives me to see the truth. I understand that to be my obligation. I also understand it to be my obligation to exemplify and to practice the virtue of intellectual humility. I need to get better at it, but I try and I understand that that's important because the one thing I can be absolutely sure about is my own fallibility. And anybody who recognizes his or her own fallibility recognizes that the only way that they're going to be able to make any progress toward eliminating the falsehoods they happen to believe and swapping out those falsehoods for truth is by allowing their beliefs to be challenged by other people and to engage those other people in a genuine truth-seeking spirit. Don't try to shut them down, but also don't turn your back to them and refuse to listen. Somebody who recognizes his own fallibility and understands that he could be wrong not only about the minor, superficial, trivial things of life, but even about the big, important things of life, the most significant questions, will want other people to be free to challenge him so that he can test his views and see if they need to be revised or replaced. So I engage my colleagues in that spirit. I am certainly willing to listen, but I expect them to listen as well. I have found that when you develop a reputation very early on from the beginning of being someone who can't be intimidated, can't be rolled, can't be, as they say today, canceled, the mob leaves you alone. They know they can't get you, so they'll move on to someone else. I liken it to the burglar. If the burglar sees that a particular house in a neighborhood is well defended, it's got an alarm system and so forth, it's not gonna bother trying to figure out how to beat the alarm system. It's gonna go on to the next house, the one that's undefended, that doesn't have the alarm system. And I'm afraid it works that way when it comes to academic life and the imposition of dogmas as well. If you're a faculty member who has a reputation for not being afraid of them, not being afraid of the mob, being unwilling to be intimidated or rolled, then move on to the next guy.

Scott: Yeah, it probably doesn't hurt

À¶Ý®ÊÓƵ

À¶Ý®ÊÓƵ